When you hear the word brain tumor, it’s easy to imagine one thing: a deadly, fast-growing mass. But the reality is far more complex. Brain tumors aren’t all the same. Some grow slowly over years, others spread aggressively within weeks. Some can be cured with surgery alone. Others need a mix of drugs, radiation, and cutting-edge targeted therapies. Understanding the difference isn’t just medical jargon-it’s the key to knowing what to expect, what treatments are possible, and what hope looks like today.

Not All Brain Tumors Are the Same: Types and Origins

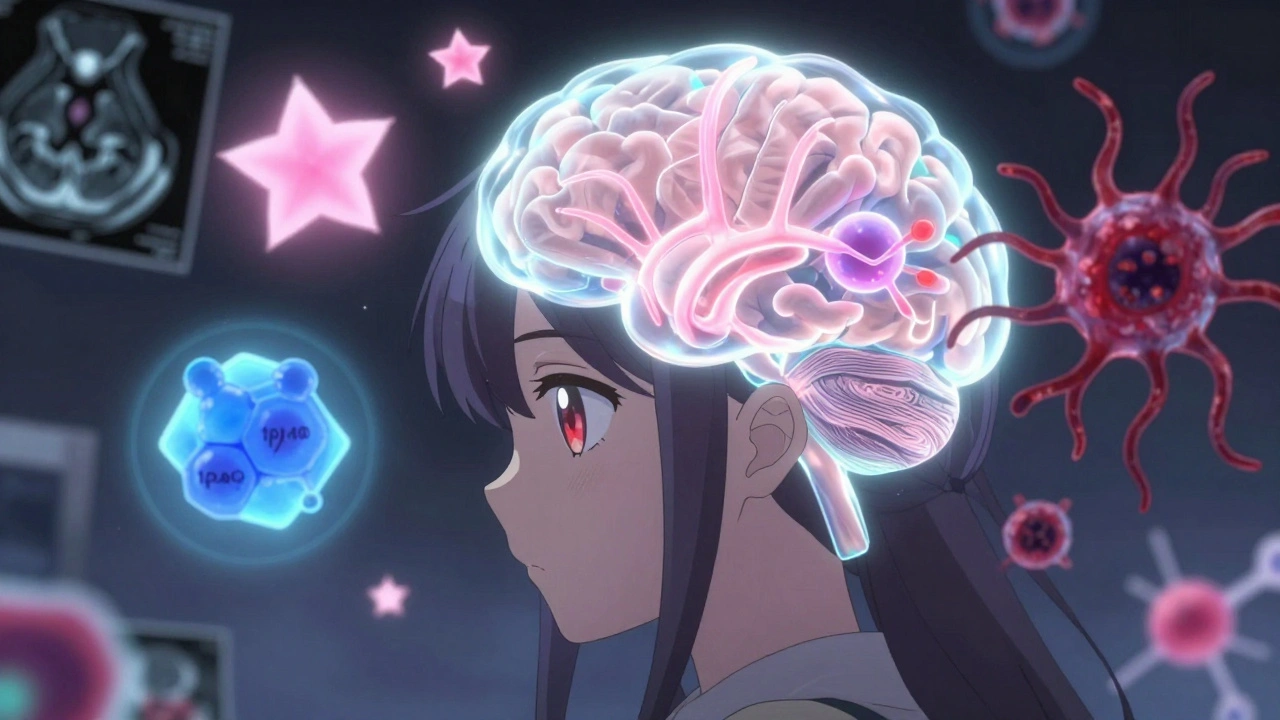

Brain tumors start in different cells, and where they begin tells doctors a lot about how they’ll behave. The most common types come from glial cells-support cells in the brain. These are called gliomas. Within that group, there are three main subtypes: astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and ependymomas.

Astrocytomas form from star-shaped cells called astrocytes. They range from slow-growing grade 2 tumors to the most aggressive form: glioblastoma, which is always grade 4. Glioblastomas make up more than half of all malignant brain tumors in adults. They grow quickly, invade nearby tissue, and often develop their own blood supply to fuel growth. Even with treatment, survival is measured in months.

Oligodendrogliomas come from cells that wrap around nerve fibers to help them send signals. These tumors are often slower growing and have a unique genetic signature: a deletion on chromosomes 1p and 19q. When this codeletion is present, the tumor responds better to chemotherapy and tends to live longer. In fact, some patients with this type survive for over a decade.

Meningiomas are different. They don’t come from brain cells at all. They grow from the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. Most are benign (grade 1), slow-growing, and can often be removed completely with surgery. But about 1 in 5 are grade 2 or 3, meaning they can come back or spread into brain tissue. Unlike gliomas, meningiomas are more common in women and often linked to hormonal factors.

Then there are rarer types-like medulloblastomas in children, or solitary fibrous tumors-that each have their own behavior patterns and treatment paths. The point isn’t to memorize them all. It’s to understand that a brain tumor’s origin shapes everything that comes next: how it’s graded, how it’s treated, and what outcomes to expect.

Grades Matter More Than You Think: WHO CNS5 Explained

Before 2021, doctors graded brain tumors based mostly on how abnormal cells looked under a microscope. That changed with the World Health Organization’s fifth edition (WHO CNS5). Now, molecular testing is just as important as what you see with a lens.

Grades range from 1 to 4. Grade 1 tumors look almost normal. They’re often found in children-like pilocytic astrocytomas-and can be cured with surgery alone. Grade 2 tumors look slightly abnormal. They grow slowly but can creep into healthy brain tissue. Left untreated, they often turn into higher-grade tumors over time.

Grade 3 tumors are called anaplastic. The cells are multiplying fast, invading nearby areas, and almost always come back after treatment. Grade 4 is the most aggressive. Glioblastoma is the classic example. It doesn’t just grow-it creates dead zones in the center of the tumor (called necrosis) and sprouts new blood vessels to feed itself.

The big shift in WHO CNS5 is that grading is now tied to tumor type. Before, an anaplastic astrocytoma was automatically grade 3. Now, you can have an astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, grade 2, or grade 4. That’s because molecular markers change everything. An IDH-mutant glioblastoma (grade 4) behaves very differently from an IDH-wildtype one. The former has a median survival of about 31 months. The latter? Just 14.6 months.

Doctors now combine histology (what cells look like) with molecular data (IDH mutation, 1p/19q codeletion, MGMT methylation) to give a single integrated diagnosis. This isn’t just fancy science-it changes treatment choices. For example, if a tumor has MGMT promoter methylation, it’s more likely to respond to temozolomide, a common chemo drug.

How Diagnosis Works: From Biopsy to Final Report

Getting a brain tumor diagnosis isn’t quick. It usually starts with an MRI scan showing a mass. But MRI can’t tell you the type or grade. That requires a biopsy or surgical removal of tissue.

The tissue goes to a neuropathology lab. First, it’s sliced thin, stained, and examined under a microscope. Then, molecular tests begin. Tests for IDH mutations, 1p/19q codeletion, and MGMT methylation are now standard. These tests can take 7 to 10 business days. Add in the time to schedule surgery and get results back, and many patients wait weeks for a full diagnosis.

Cost is a hidden factor. In the U.S., comprehensive molecular testing adds $3,200 to $5,800 to the diagnostic bill. Insurance usually covers it, but not everywhere. In countries with limited resources, patients may never get these tests, and their treatment is based on guesswork.

There’s progress. The FDA approved the Ventana IDH1 R132H antibody in 2021. It’s a simple stain that gives results in 48 hours instead of weeks. That’s a game-changer for planning surgery and starting treatment faster.

Pathologists needed time to adapt. One study found it took an average of 17.3 cases before they reached 90% accuracy with the new WHO CNS5 system. It’s not just about reading slides anymore. It’s about reading DNA.

Treatment Today: The Multimodal Approach

There’s no single cure for brain tumors. Treatment is almost always a combination-multimodal-of surgery, radiation, and drugs. The goal isn’t always to eliminate the tumor. Sometimes, it’s to slow it down, control symptoms, and give you more time with quality of life.

Surgery is the first step whenever possible. If the tumor is in a safe area, removing as much as possible improves outcomes. But some tumors, especially grade 4 glioblastomas, are like roots in soil-they spread into healthy tissue. You can’t cut them all out without damaging critical brain functions.

Radiation comes next. It’s used to kill leftover cells. For low-grade tumors, radiation might be delayed for years. For high-grade tumors, it starts right after surgery. Standard radiation lasts 6 weeks, but newer techniques like proton therapy can target tumors more precisely, sparing healthy brain tissue.

Chemotherapy is often used alongside radiation. Temozolomide is the go-to drug for glioblastoma. It works best if the tumor has MGMT promoter methylation. For oligodendrogliomas, a combo of PCV (procarbazine, lomustine, vincristine) can be more effective than temozolomide.

But the biggest breakthroughs are in targeted therapy. In June 2023, the FDA approved vorasidenib for grade 2 gliomas with IDH mutations. In the INDIGO trial, patients on vorasidenib had 27.7 months without tumor growth-nearly triple the 11.1 months for those on placebo. That’s not just an extension of life. It’s a delay in needing radiation or chemo, which can damage the brain over time.

For patients with IDH-mutant grade 4 astrocytoma, this drug is now being tested in clinical trials. Early results suggest it could extend survival even in advanced cases.

What Patients Are Saying: Real Experiences

Behind every diagnosis is a person. On Reddit’s r/BrainTumors community, one user, diagnosed at 32 with a grade 2 oligodendroglioma, said they had only 72 hours to decide on fertility preservation before surgery. That’s the reality: treatment decisions aren’t just medical-they’re personal, urgent, and life-altering.

A 2022 survey by The Brain Tumour Charity found 68% of patients waited more than 8 weeks for a diagnosis. People with low-grade tumors waited longer-14 weeks on average-because doctors often assumed it was something less serious. That delay can mean the difference between catching a tumor before it spreads and having to treat an advanced one.

One patient, ‘GBMWarrior87’, shared on the National Brain Tumor Society forum that vorasidenib gave them 18 months without progression-longer than the standard 14.6 months. That’s not just hope. That’s data turning into real time.

But confusion still runs deep. A study found 42% of patients thought a grade 2 tumor meant a 20% chance of survival. It doesn’t. Grade 2 means slow growth. Many live 10, 15, even 20 years. The numbers don’t define you. The treatment plan does.

The Future: Liquid Biopsies and Personalized Medicine

What’s next? Liquid biopsies. Instead of cutting into the brain, doctors are testing cerebrospinal fluid for tumor DNA. A 2023 study in Nature Medicine showed 89% accuracy in detecting tumor markers this way. That could mean fewer invasive surgeries and earlier detection of recurrence.

The CODEL trial, still ongoing, is testing whether combining chemo and radiation gives better results for oligodendroglioma than either alone. Results are expected by late 2024.

And the grading system? It’s still evolving. The WHO has revised its classification five times since 1979. Each update adds precision. The next one may include immune markers, gene expression profiles, or even AI-assisted analysis of tumor images.

What’s clear is this: brain tumors are no longer one-size-fits-all. Treatment is becoming as unique as your DNA. The future isn’t about fighting the tumor-it’s about outsmarting it, one mutation at a time.

What’s the difference between a low-grade and high-grade brain tumor?

Low-grade tumors (grades 1 and 2) grow slowly, have well-defined edges, and rarely spread to other brain areas. They’re often treatable with surgery alone or with minimal radiation. High-grade tumors (grades 3 and 4) grow fast, invade healthy tissue, and almost always come back. Grade 4 tumors, like glioblastoma, are aggressive cancers that require a mix of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Molecular markers now help predict how each tumor will behave, even within the same grade.

Can a grade 2 brain tumor become grade 4?

Yes. Grade 2 tumors, especially astrocytomas without IDH mutations, can transform into higher-grade tumors over time-sometimes in years, sometimes in decades. That’s why regular MRI scans are critical, even if the tumor seems stable. Molecular testing helps predict this risk. For example, an IDH-mutant grade 2 tumor is much less likely to turn aggressive than one without the mutation.

Why is molecular testing so important for brain tumors?

Molecular testing tells doctors what the tumor is made of at the genetic level. A tumor that looks like a grade 3 astrocytoma under the microscope might actually be an IDH-mutant tumor with better outcomes. Or it might be IDH-wildtype, meaning it’s really a hidden glioblastoma. Without these tests, treatment is based on guesswork. With them, doctors can pick the right drugs, avoid unnecessary radiation, and offer targeted therapies like vorasidenib.

Is surgery always the first step for brain tumors?

Not always. If the tumor is in a critical area-like the brainstem or near speech centers-surgery might be too risky. In those cases, doctors may start with radiation or targeted drugs. For low-grade tumors that aren’t causing symptoms, some patients are monitored with regular MRIs instead of rushing into surgery. The goal is to balance removing the tumor with preserving brain function.

What’s the survival rate for glioblastoma today?

For IDH-wildtype glioblastoma (the most common type), the median survival is 14.6 months with standard treatment (surgery, radiation, temozolomide). About 5% of patients live five years or longer. But for IDH-mutant glioblastoma, survival jumps to around 31 months. New drugs like vorasidenib are extending those numbers even further, especially when used earlier in the disease. Survival isn’t a fixed number-it’s shaped by genetics, treatment timing, and access to clinical trials.

Are there new treatments approved in 2024?

As of early 2025, the most significant recent approval is vorasidenib for IDH-mutant grade 2 gliomas, approved by the FDA in June 2023. It’s the first drug shown to significantly delay tumor growth without needing radiation or chemo right away. Clinical trials for new drugs targeting other mutations (like EGFR, BRAF, or NTRK) are underway. While no new FDA approvals came in 2024, several are expected by late 2025, especially for pediatric tumors and recurrent glioblastoma.

What Comes Next: Staying Informed and Advocating for Care

Knowledge is power. If you or someone you know has been diagnosed, ask for molecular testing. Ask what the IDH status is. Ask if MGMT methylation was checked. Don’t accept a diagnosis without it. These results determine your options.

Connect with patient advocacy groups. The National Brain Tumor Society, The Brain Tumour Charity, and the Brain Tumor Foundation offer free resources, clinical trial matching, and peer support. Many patients find comfort in knowing they’re not alone-and that progress is real.

The future of brain tumor care isn’t just in labs. It’s in the hands of patients who ask the right questions, demand comprehensive testing, and push for access to new treatments. Every step forward-whether it’s a new drug, a faster test, or a clearer diagnosis-comes from people who refused to accept the old limits.

Comments (8)

Ollie Newland

Just read through this and had to pause. The IDH-mutant vs wildtype survival gap is insane-31 months vs 14.6? That’s not just a statistic, that’s someone’s extra two years with their kid’s graduation, their wedding anniversary, their dog’s last walk. Molecular testing isn’t luxury, it’s life insurance.

And vorasidenib? Holy hell. Delaying radiation for 27+ months? That’s not just buying time-it’s preserving cognition, memory, personality. We’ve been treating brain tumors like they’re just tumors. Turns out they’re more like corrupted software-patch the code, not just smash the hardware.

Rebecca Braatz

THIS. RIGHT. HERE. 🙌 If you or someone you love has a brain tumor, DO NOT accept a diagnosis without IDH and MGMT testing. I’m screaming into the void but I’ll say it again: your doctor might not know the latest WHO CNS5 guidelines. Push. Demand. Bring this article. Your survival isn’t a guess-it’s a code you can crack. And if they say ‘it’s too expensive’? Tell them to bill your insurance. This isn’t optional. It’s survival math.

Benjamin Sedler

Okay but let’s be real-how many of these ‘breakthroughs’ are just pharma’s way of selling you a $200k/year pill that works for 3% of people? Vorasidenib sounds great, but I’ve seen this movie before. ‘Miracle drug’ → six months later → ‘Oh, it only works if you’re under 55, have no liver issues, and your tumor has exactly this one mutation.’

Also, ‘liquid biopsies’? Cool. Now tell me how many rural folks in Alabama get that when their MRI shows a ‘possible mass’ and their neurologist says ‘come back in six months.’

Alex Piddington

It is imperative to underscore the significance of molecular diagnostics in the modern management of central nervous system neoplasms. The paradigm shift from histology-based to integrated molecular-histological classification, as formalized by WHO CNS5, represents a monumental advancement in precision oncology.

One must acknowledge the logistical and economic disparities in access to such testing, particularly in low-resource settings. The cost differential of $3,200–$5,800 per case is not trivial, and it is lamentable that equitable access remains unachieved. Nevertheless, the scientific progress is undeniable, and the trajectory toward personalized, mutation-targeted therapies is both promising and ethically imperative.

Emmanuel Peter

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me a 32-year-old had 72 hours to decide if they wanted to freeze their eggs before brain surgery, and now we’re all supposed to be like ‘aww, how brave’ while the healthcare system still makes people wait 14 weeks for a diagnosis?

Meanwhile, the guy who wrote this article probably gets a free MRI every year because he’s got good insurance and a neurologist on speed dial. Real talk: this isn’t about ‘hope’-it’s about who gets the fancy tests and who gets told to ‘wait and see’ until it’s too late.

Chad Handy

Look, I’ve been through this. My brother had a grade 2 astrocytoma, IDH-mutant, MGMT methylated. They told us ‘it’s slow-growing, you’re good.’ Two years later, boom-grade 4. No warning. No symptoms. Just a scan that said ‘you’re now terminal.’

And yeah, vorasidenib sounds amazing. But he died before it was approved. He was on a waiting list for a clinical trial for 11 months. They said ‘it’s not ready for you yet.’

So don’t talk to me about ‘hope’ like it’s a magic spell. Hope doesn’t pay the mortgage. Hope doesn’t stop your kid from asking why you’re always tired. Hope doesn’t bring back the time you lost waiting for a biopsy.

What I want is faster access. Cheaper tests. Less bureaucracy. Less waiting. Less ‘we’ll try this next year.’

And if you’re a doctor reading this? Don’t wait for the guidelines to catch up. Test. Now. Even if it’s not ‘standard.’

My brother’s name was Daniel. He was 37. He didn’t get the new drug. He got the old system.

Chase Brittingham

Chad, I hear you. And I’m so sorry about Daniel. That’s the part no one talks about-the silence between the diagnosis and the treatment, when you’re just waiting for the other shoe to drop.

But I also want to say this: the people pushing for faster testing, for better access, for clinical trials in rural hospitals-they’re not just doctors or researchers. They’re people like you. People who lost someone. People who refuse to let it be normal to wait 14 weeks.

There’s a movement growing. Advocacy groups are demanding change. Labs are cutting turnaround times. Insurance companies are finally starting to cover liquid biopsies. It’s slow, but it’s real.

Daniel’s story isn’t just a tragedy. It’s a catalyst. And that matters.

Bill Wolfe

Wow. Just... wow. 😏 I’m impressed by how this post managed to turn a complex oncology topic into a feel-good TED Talk with a side of corporate-sponsored hope.

Let’s not forget: glioblastoma is still a death sentence for 95% of patients. Vorasidenib? A Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. Liquid biopsies? Cool tech for the 1% who can afford it. And don’t even get me started on the ‘patient advocacy’ fairy tale-those groups are funded by the same pharma companies selling you the $500,000 drug.

Meanwhile, the real issue? We still don’t know why brain tumors form. We don’t have prevention. We don’t have early detection. We just have better ways to make people feel like they’re getting ‘hope’ while the clock ticks.

So yeah. Celebrate the 1% survival bump. I’ll be over here, watching the real numbers: 12,000 new cases a year in the US. 12,000 families shattered. And zero cure.

But hey-at least now we have a 27-month delay. 🎉