By age 3, most children can point to their eyes and say "I see." But what if they can’t see clearly - and don’t even know it? That’s the silent risk behind pediatric vision screening. Vision problems like amblyopia (lazy eye) and strabismus (crossed eyes) don’t always come with crying, squinting, or complaints. Kids adapt. They learn to see the world through one eye, or tilt their head to compensate. Left undetected, these conditions can lead to permanent vision loss - and it’s entirely preventable.

Why Screening Before Age 5 Matters More Than You Think

The human visual system is most flexible in early childhood. Between birth and age 7, the brain is still wiring itself to interpret what the eyes see. If one eye is blurry or misaligned, the brain starts ignoring it. That’s amblyopia. By age 8, that window closes. Treatment becomes harder, less effective, and sometimes impossible. Studies show that when amblyopia is caught before age 5, 80-95% of children can regain normal vision with treatment. After age 8, that number drops to just 10-50%. The Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) study, which tracked over 1,000 children from 2002 to 2008, proved this isn’t theoretical - it’s measurable. And it’s why organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend screening all children between ages 3 and 5.What Gets Screened - And How

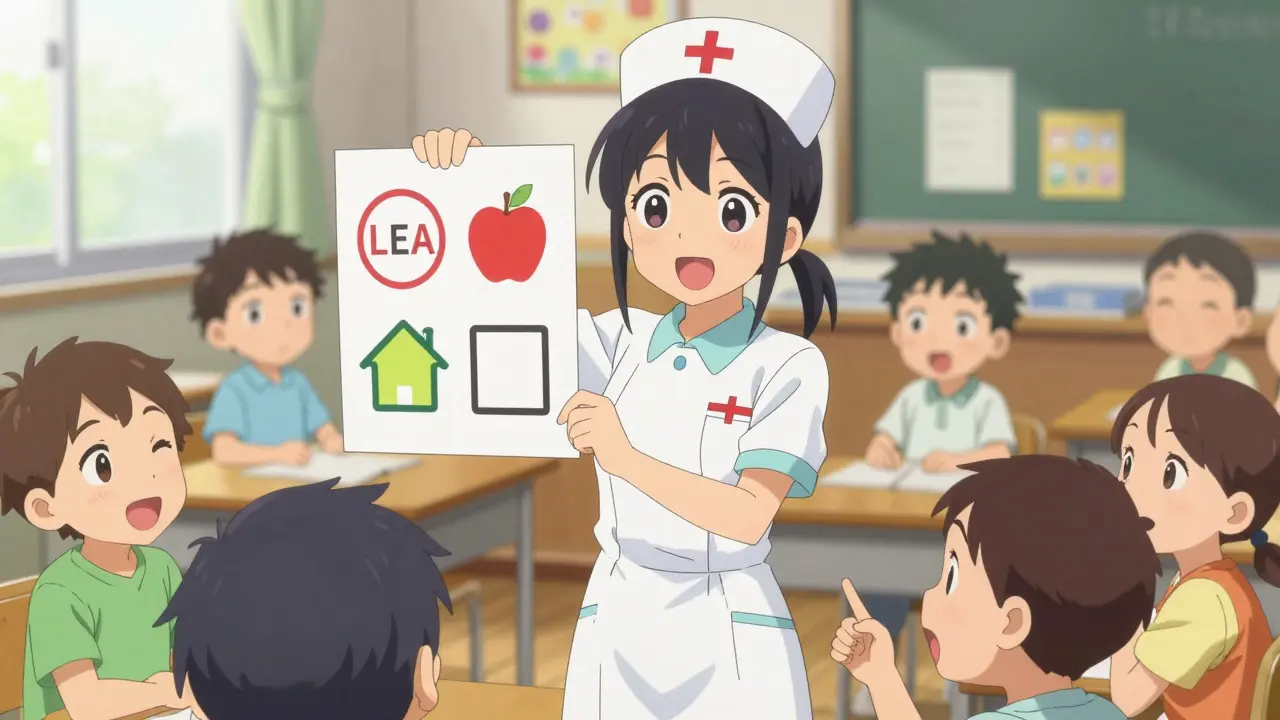

Not every child needs a full eye exam. Vision screening is a quick, low-cost check to find who needs further testing. The goal isn’t to diagnose - it’s to flag risk. For infants under 6 months, providers use the red reflex test. A light is shone into each eye. A healthy eye reflects a bright red glow. A dull, white, or uneven reflection can signal cataracts, retinoblastoma (a rare eye tumor), or other serious conditions. This takes seconds and requires no cooperation from the baby. From 6 months to 3 years, screening focuses on three things: red reflex, eye movement, and eyelid health. Is one eye turning in or out? Are the pupils reacting the same? Is there a droopy lid blocking vision? These signs are red flags. Starting at age 3, visual acuity testing begins. This is where charts come in. But not just any chart. For toddlers, symbols like LEA symbols (circles, squares, apples, houses) or HOTV letters (H, O, T, V) are used because kids can’t read yet. By age 5, most can use the Sloan letters chart - the gold standard for older children. Here’s what success looks like:- Age 3: Must identify most symbols on the 20/50 line

- Age 4: Must pass the 20/40 line

- Age 5+: Must read the 20/32 line (or 20/30 on Snellen charts)

Instrument-Based Screening: The New Standard for Young Kids

Not every 3-year-old will sit still for a chart. That’s where instrument-based screening shines. Devices like the SureSight autorefractor, Power Refractor, and the newer blinq™ scanner take a snapshot of how light reflects off the retina. In seconds, they detect refractive errors (nearsightedness, farsightedness, astigmatism) and misalignment - even if the child won’t look at a picture. The blinq™ scanner, cleared by the FDA in 2018, has shown 100% sensitivity for detecting referral-warranted conditions in kids aged 2-8. That means it misses almost nothing. It’s also fast - under two minutes per child - and doesn’t need verbal responses. Research in American Family Physician (2023) found instrument-based screening has a 68% positive predictive value in 3- to 4-year-olds, compared to just 52% for traditional chart tests. That means fewer false alarms and fewer unnecessary referrals. But here’s the catch: these devices can overcall. A child with a tiny, harmless refractive error might trigger a referral. That’s why experts still recommend combining methods. If an instrument flags a problem, follow up with a chart test. If the child passes the chart but the device says “refer,” don’t ignore it - refer anyway.

What Happens When Screening Fails

Screening isn’t perfect. About 10-25% of 3- to 4-year-olds won’t cooperate with chart tests. Poor lighting, wrong distance, or an untrained screener can cause false negatives. One 2018 study found 25% of screenings had improper chart illumination. Another found 20% of false positives came from incorrect distance measurement. That’s why training matters. Providers need 2-4 hours of certified training to get it right. The National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health (NCCVEH) offers free online modules used by over 15,000 professionals since 2016. Schools, pediatric clinics, and Head Start programs should all have trained staff. And when screening fails? That’s when referrals become critical. A child flagged by screening needs a full eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist or optometrist. That’s not optional. Delaying that exam by months - or years - can mean the difference between restored vision and lifelong impairment.Who Gets Screened - And Who Doesn’t

In the U.S., 85% of children under 18 get some form of vision screening during well-child visits. That sounds good - until you look closer. The National Survey of Children’s Health (2019) found Hispanic and Black children are 20-30% less likely to receive recommended screening. Poverty, lack of access to pediatric care, language barriers, and misinformation all play a role. A child in rural Mississippi or inner-city Detroit might never see a pediatrician between ages 3 and 5 - and that’s where the risk spikes. Thirty-eight states require school-entry vision screening, but standards vary wildly. Some test only distance vision. Others skip near vision. A few still use outdated Snellen charts with letters too small for preschoolers. The result? Kids slip through. The economic case is clear. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force calculated a benefit-cost ratio of 3.7:1 for pediatric vision screening. That means for every $1 spent, $3.70 in lifetime costs are saved - from special education to lost productivity. Untreated amblyopia costs an estimated $1.2 billion annually in the U.S. alone.

What Comes Next - And How to Stay Ahead

The future of pediatric vision screening is moving younger. A 2022 study in JAMA Pediatrics showed instrument-based screening can be reliably done as early as 9 months. The American Academy of Pediatrics is expected to update its guidelines by 2025 to reflect this. If screening starts at 12 months instead of 3 years, we could catch even more cases before the brain locks in faulty vision. Artificial intelligence is now part of the toolkit. The blinq™ scanner uses AI to analyze retinal images and predict risk. More devices like this are coming. The National Eye Institute has invested $2.5 million (2021-2024) to improve accuracy in diverse populations - because equity matters. A screening tool that works well for one group but fails for another isn’t just ineffective - it’s unfair. For parents, the message is simple: Don’t wait for symptoms. Ask for vision screening at every well-child visit from age 1 onward. If your child’s pediatrician doesn’t offer it, ask why. If they say, "They’re too young," push back. The evidence is clear - screening starts early, and it saves sight.What Parents Should Do

- Ask for vision screening at every well-child checkup starting at age 1

- Know the signs: squinting, head tilting, closing one eye, poor eye contact

- Don’t assume school screenings are enough - they often miss key issues

- If your child fails screening, get a full eye exam within 1-2 months

- Even if your child passes, monitor for changes - vision can change fast

Every child deserves to see the world clearly. Vision screening isn’t a luxury. It’s a basic health check - like hearing tests or blood pressure. Skip it, and you risk more than blurry vision. You risk a lifetime of unseen limits.

What is the most common vision problem in young children?

The most common vision problem in children under 6 is amblyopia, or "lazy eye." It affects 1.2% to 3.6% of kids. Strabismus (misaligned eyes) is the second most common, affecting about 1.9% to 3.4%. Both can be corrected if caught early - but not after age 7.

Can a child pass a school vision screening and still have a problem?

Yes. School screenings often only check distance vision and use outdated methods. Many miss near vision problems, astigmatism, or subtle eye misalignment. A child can pass a school test but still need glasses or treatment for amblyopia. A full eye exam by a pediatric eye specialist is the only way to be sure.

Is vision screening covered by insurance?

Yes. Under the Affordable Care Act, pediatric vision screening is an essential health benefit. Most private plans and Medicaid programs cover it as part of well-child visits. Some states require it by law. If you’re asked to pay out-of-pocket, ask if it’s billed as a preventive service - it shouldn’t cost you anything.

How often should a child be screened for vision problems?

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening at ages 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, and 15 years. The most critical window is between 3 and 5, when the brain is still developing vision. After age 5, screenings every 2 years are standard unless a problem is found.

What if my child refuses to cooperate during screening?

It’s common - especially with 3-year-olds. If your child won’t look at a chart, ask if instrument-based screening is available. Devices like the blinq™ scanner or SureSight don’t require cooperation. They work in seconds while your child sits on your lap. If neither is available, try again in a few weeks. Don’t give up - early detection saves sight.

Comments (9)

Elaine Douglass

I had no idea vision screening could be this critical before age 5. My daughter passed her school test at 4 but we didn’t catch her lazy eye until she was 6. It’s scary how easy it is to miss.

Now she wears glasses and her confidence has sky-rocketed. Just ask your pediatrician - don’t wait for symptoms.

Nicole Rutherford

Ugh. Another government-mandated checklist disguised as healthcare. My kid got screened at 3 and 4 and 5 and still got glasses at 7. All that screening just means more paperwork and less time playing.

Monte Pareek

Let me tell you something real - vision screening isn’t optional, it’s foundational. I’m a pediatric nurse in rural Ohio and I’ve seen kids who couldn’t see the board until they were 10 because no one ever checked.

Instrument-based tools like blinq™ are game-changers. One kid in my clinic had a tumor we caught because the device flagged it - he’s 12 now and sees fine. No chart test would’ve caught that.

Don’t let ‘they’re too young’ be an excuse. The brain wires itself by age 7. After that? You’re just managing damage. Screening isn’t about checking boxes - it’s about preserving a child’s entire future. Every parent deserves to know this. Every provider needs to do this. No excuses.

And yes, I’ve trained over 200 staff members on this. It’s not hard. It’s just not prioritized. Fix that.

And if your kid’s school only tests distance vision? That’s not screening - that’s negligence. Demand better.

William Storrs

My son was diagnosed with amblyopia at 4 after his pediatrician used the SureSight. We were lucky. Not everyone is. But here’s the thing - if you’re reading this, you already care. That’s half the battle.

Ask for screening at every visit. Even if they say ‘no need.’ Even if they say ‘he’s fine.’ Push. You’re not being annoying - you’re being a parent.

And if you’re a provider? Do the work. Training is free. Tools exist. Stop making excuses. These kids are counting on you.

Dorine Anthony

My cousin’s kid missed screening entirely because they moved and the new doctor didn’t offer it. He’s 8 now and still has poor depth perception. It’s heartbreaking. This isn’t just medical - it’s social justice.

Anna Sedervay

It is, of course, imperative to underscore the epistemological imperative of early visual acuity assessment, as the ontological development of ocular neural pathways is irrevocably contingent upon timely intervention. The empirical validity of the VIP study, while statistically robust, fails to account for socio-linguistic variance in parental reporting, thereby introducing a latent confounder into the causal inference model. Furthermore, the FDA clearance of the blinq™ device, while laudable, represents a technocratic overreach that privileges algorithmic determinism over clinical judgment. One must question whether the 68% positive predictive value is truly indicative of clinical utility, or merely a reflection of over-diagnosis driven by institutional incentives. The true crisis, I argue, lies not in screening, but in the commodification of pediatric health under neoliberal healthcare paradigms.

Dominic Suyo

Oh wow. Another 2000-word manifesto dressed up as a blog post. Let me guess - you work for a vision screening startup? Or maybe you’re just a glorified medical salesman with a PowerPoint?

Instrument-based screening? Sure. But have you seen the cost? Or the false positives that send parents into panic mode? Or how half the clinics in this country use broken devices because they’re too cheap to replace them?

This isn’t medicine. It’s performance art. And the kids? They’re just props in your feel-good narrative.

James Stearns

It is a matter of profound public health significance that the American Academy of Pediatrics has not mandated universal instrument-based screening prior to age two. The current guidelines, while well-intentioned, represent a dangerous delay in intervention. The neurological plasticity of the visual cortex, as documented in peer-reviewed neurodevelopmental literature, is demonstrably maximal between the ages of 9 and 18 months. To defer screening until age three is not merely suboptimal - it is ethically indefensible. Furthermore, the omission of standardized training protocols for non-ophthalmic personnel constitutes a systemic failure of professional accountability. The economic argument, while persuasive, is insufficient. We must act not because it saves money, but because it is right.

Mark Able

My daughter failed the screening at 3. We went to the specialist and she needed glasses. But here’s the kicker - the doctor told us she’d have been fine if we’d waited. So we waited. At 5, she still couldn’t see the board. Now she’s in therapy for reading delays. Don’t listen to the ‘wait and see’ crowd. If your kid fails - go. Now.