When your blood sugar climbs above 180 mg/dL, your body starts sending warning signs-signs many people ignore until it's too late. Hyperglycemia isn't just a number on a glucometer. It's a silent crisis that can turn deadly in hours if left unchecked. For people with diabetes, especially those who skip checks or delay insulin, high blood sugar isn't an inconvenience-it's a medical emergency waiting to happen.

What Exactly Is Hyperglycemia?

Hyperglycemia is a condition where blood glucose levels rise above normal thresholds, typically above 180 mg/dL, due to insufficient insulin action or severe insulin resistance. It's not a one-time spike-it's a pattern that builds over time, often unnoticed until complications arise.

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas stops making insulin. Without it, glucose can't enter cells for energy, so it piles up in the bloodstream. In type 2 diabetes, cells ignore insulin signals, and the pancreas eventually burns out trying to compensate. Either way, glucose sits where it shouldn’t-flooding the blood, damaging vessels, and starving cells.

The American Diabetes Association says nearly 37 million Americans live with diabetes. Many don’t realize their blood sugar is dangerously high until they end up in the ER. And it’s not just diabetics-stress, illness, or certain medications like steroids can trigger hyperglycemia in people without diabetes too.

Early Warning Signs You Can’t Afford to Ignore

The first symptoms are subtle. So subtle, most people brush them off as "just tired" or "drinking too much coffee." But here’s what’s really happening:

- Polyuria: You’re peeing more than 2.5 liters a day-frequently, urgently, and often at night. Your kidneys are working overtime to flush out excess glucose.

- Polydipsia: No matter how much water you drink, you’re still thirsty. You might be consuming over 4 liters daily. Your body is trying to dilute the sugar in your blood.

- Blurred vision: High glucose swells the lenses in your eyes. It’s temporary, but it’s your body’s way of saying "something’s wrong." Studies show 68% of people with uncontrolled diabetes report this.

- Fatigue: You’re not sleeping poorly-you’re energy-starved. Glucose is everywhere, but your cells can’t use it. That’s why 79% of patients describe crushing exhaustion even after rest.

These aren’t normal. If you’re experiencing two or more of these consistently, check your blood sugar. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s stress or a bad night’s sleep.

When Symptoms Turn Dangerous

Once blood sugar hits 250 mg/dL, things escalate fast. The body starts breaking down fat for fuel because glucose is locked out of cells. That’s when ketones appear-and that’s when danger kicks in.

At this stage, you might notice:

- Headaches: 52% of patients report persistent, dull headaches as glucose toxicity affects brain fluid balance.

- Difficulty concentrating: Your brain is flooded with sugar but starved of usable energy. Studies show nearly half of type 2 patients struggle with focus at this level.

- Unexplained weight loss: Losing more than 5% of your body weight over three months without trying? That’s your body eating muscle and fat because it can’t access glucose.

These are red flags. If you’re seeing these, don’t wait until tomorrow. Test your ketones. Call your doctor. If you’re on insulin, give your correction dose-now.

The Two Life-Threatening Emergencies: DKA and HHS

When hyperglycemia hits 300 mg/dL or higher, two emergencies can occur. They look similar but are fundamentally different.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) is a rapid-onset emergency where the body produces high levels of ketones due to severe insulin deficiency, typically in type 1 diabetes. Blood glucose exceeds 250 mg/dL, blood pH drops below 7.3, and ketone levels rise above 3 mmol/L.

DKA hits fast-within 24 to 48 hours. You’ll smell acetone on your breath (like nail polish remover). You’ll breathe deep and fast-Kussmaul respirations-as your body tries to blow off acid. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain are common. It’s especially dangerous in children, who account for 70% of pediatric diabetes deaths.

Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) is a slower, deadlier emergency seen mostly in type 2 diabetes. Blood glucose soars above 600 mg/dL, serum osmolality exceeds 320 mOsm/kg, and there’s little to no ketone production.

HHS creeps up over days or weeks. Dehydration is extreme-fluid losses of 8 to 12 liters are common. Confusion, weakness, and even seizures or coma can occur. Unlike DKA, there’s no fruity breath. Instead, you’ll see dry skin, sunken eyes, and a racing heart. Mortality rates? 15-20%. That’s higher than DKA’s 1-5%.

Why the difference? DKA mostly affects younger people with type 1. HHS hits older adults with type 2, often with other illnesses like infections or heart failure. And here’s the cruel twist: many HHS patients don’t even know they have diabetes until they’re in the ICU.

What Triggers a Hyperglycemic Emergency?

It’s rarely just "forgetting insulin." Real triggers are more complex:

- Infection or illness: Fever, pneumonia, UTIs-any stressor spikes cortisol and adrenaline, which push glucose up. This causes 42% of severe episodes.

- Insulin pump failure: A clogged catheter or empty reservoir can shut off insulin delivery. 18% of emergencies trace back to this.

- Carb-counting errors: Eating a pizza without adjusting insulin? That’s 29% of cases.

- Medications: Steroids, some antipsychotics, and even decongestants can raise glucose by 50-100 mg/dL.

- Emotional stress: Grief, trauma, or chronic anxiety raise cortisol. This triggers hyperglycemia in 11% of cases.

- Dawn phenomenon: Between 4 and 8 a.m., natural hormones spike glucose by 30-50 mg/dL. Many people don’t realize this is why their fasting sugar is always high.

And here’s something rarely talked about: gastroparesis. A condition where the stomach empties slowly. It delays insulin absorption, causing delayed spikes. One study found 19% of people with recurrent hyperglycemia had undiagnosed gastroparesis.

What to Do in an Emergency

If your blood sugar is over 240 mg/dL, don’t panic-but don’t delay either.

- Test for ketones: Use urine strips or a blood ketone meter. If ketones are moderate to high (above 1.5 mmol/L), treat as DKA.

- Take insulin: If you’re on insulin, give your correction dose. Most people need 0.1 units per kg of body weight every hour until glucose drops below 250 mg/dL. Don’t skip this.

- Hydrate: Drink 8-16 oz of sugar-free fluids every hour. Water, electrolyte solutions, or sugar-free tea. Avoid sugary drinks-even if you’re thirsty, sugar makes it worse.

- Don’t exercise: Physical activity can raise glucose further if ketones are present. Wait until levels are under control.

- Call for help: If you’re vomiting, confused, breathing hard, or your glucose is above 300 mg/dL with ketones, go to the ER. Don’t wait for someone else to tell you it’s serious.

Many people delay because they think they "can handle it." But hyperglycemia doesn’t care about your confidence. It only cares about your glucose level.

How to Prevent It

Prevention isn’t about perfection. It’s about consistency.

- Check blood sugar regularly: Test at least twice daily. If you’re sick, test every 4 hours.

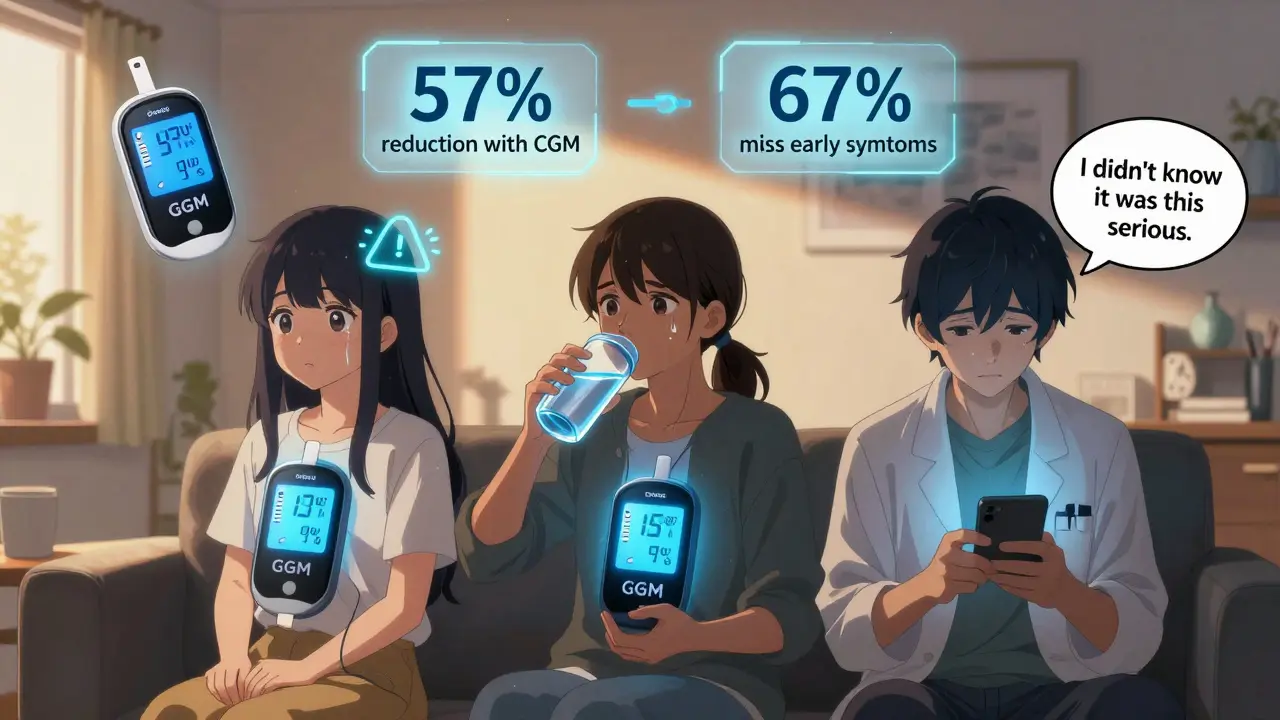

- Use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM): CGM users reduce severe hyperglycemia by 57%. Real-time alerts catch spikes before they become emergencies. The new Dexcom G7 even predicts highs 30 minutes ahead.

- Know your insulin-to-carb ratio: Most people need 1 unit per 10-15 grams of carbs. Work with your provider to find yours.

- Adjust for the dawn phenomenon: If your morning sugar is always high, talk to your doctor about adjusting your basal insulin.

- Get educated: Programs like the CDC’s Diabetes Self-Management Education cut ER visits by 42%. Knowledge saves lives.

And here’s a hard truth: 67% of people don’t recognize symptoms until their blood sugar is over 300 mg/dL. That’s too late. Learn your body’s early signals. Write them down. Share them with your family.

What’s Changing Now

The field is moving fast. In January 2024, the FDA approved Dexcom G7’s "Glucose Guardian"-an algorithm that predicts hyperglycemia before it happens. It’s already cutting severe highs by 31%.

The NIH just launched a $150 million initiative to use AI and wearables for early detection. By 2025, guidelines will relax targets for seniors over 65-keeping fasting glucose under 180 mg/dL instead of 130-to avoid dangerous lows.

But access remains unequal. Black patients experience 2.3 times more hyperglycemia emergencies than white patients-not because of biology, but because of insulin access, cost, and care gaps.

By 2030, experts predict integrated digital health platforms could cut hyperglycemia incidents by 60%. But that future only works if everyone has access to the tools.

Final Thought

High blood sugar isn’t a personal failure. It’s a physiological crisis. You didn’t "mess up." Your body is signaling that something needs fixing. The goal isn’t perfection-it’s awareness. Early action. Consistent checks. And never ignoring the signs.

Every minute counts. Every test matters. And every time you act, you’re not just lowering a number-you’re saving your future.

What blood sugar level is considered hyperglycemia?

Hyperglycemia is generally defined as a blood glucose level above 180 mg/dL. Mild cases range from 180-250 mg/dL, moderate from 251-300 mg/dL, and severe is above 300 mg/dL. Emergencies occur above 600 mg/dL, especially with ketones or extreme dehydration.

Can non-diabetics have hyperglycemia?

Yes. Infections, severe stress, steroids, pancreatitis, or Cushing’s syndrome can cause temporary hyperglycemia in people without diabetes. These cases often resolve once the trigger is treated, but they can still be dangerous and require medical attention.

What’s the difference between DKA and HHS?

DKA (diabetic ketoacidosis) happens mostly in type 1 diabetes with high ketones, acidosis, and rapid onset. HHS (hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state) occurs in type 2 diabetes with extreme dehydration, very high glucose (>600 mg/dL), no significant ketones, and slower progression. HHS has a higher death rate, especially in older adults.

Should I exercise if my blood sugar is high?

Only if ketones are negative. If your blood sugar is above 250 mg/dL and you have moderate to high ketones, avoid exercise-it can make hyperglycemia worse. Wait until your glucose drops below 250 mg/dL and ketones are gone before being active.

How can I prevent recurrent hyperglycemia?

Use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) for real-time alerts, test blood sugar regularly, know your insulin-to-carb ratio, adjust for the dawn phenomenon, and treat infections immediately. Education programs like the CDC’s Diabetes Self-Management Education can reduce episodes by over 40%.

Why do some people with type 2 diabetes go into HHS without knowing they have diabetes?

Many type 2 diabetes cases are undiagnosed because symptoms develop slowly. Fatigue, thirst, and frequent urination are often mistaken for aging or stress. By the time HHS occurs, the person may have had high blood sugar for months or years without testing. This is why routine screening, especially for those over 45 or with risk factors, is critical.

Comments (12)

Rob Turner

Man, I read this and just thought about my uncle in Birmingham who went undiagnosed for years. He thought he was just getting old-tired all the time, peeing every hour, drinking soda to quench his thirst. One day he passed out in the kitchen. Turned out his sugar was 580. They had to ICU him for a week. This post? It’s the warning we all need but don’t want to hear. 😔

Gabriella Adams

I work in endocrinology. Let me tell you-DKA is terrifying because it moves faster than a sprinter on caffeine. But HHS? That’s the silent killer. Elderly patients, often alone, with no one checking their sugars. I had a 78-year-old come in last month with a glucose of 942. No ketones. No complaints. Just... confused. She didn’t know she was diabetic. We saved her. But not everyone gets that lucky. Please. Test. Talk. Act.

Suzette Smith

Okay but what if it’s just because you ate a donut? Like, come on. I had a sugar spike once after pizza and I panicked. Turned out I was just dehydrated. Maybe we’re over-medicalizing normal human behavior?

andres az

They say 'insulin resistance' like it's a medical fact. But have you ever looked at the FDA's 2018 white paper on glucose metrics? The 180 mg/dL threshold was pulled from a 1979 study funded by Big Pharma. The real danger is insulin dependency. The system wants you dependent. CGMs? $1,000/month. You think that’s coincidence? Wake up.

Stephon Devereux

I’m a type 1 for 22 years. This is the most accurate summary I’ve read. The dawn phenomenon? Yeah. Every. Single. Morning. I used to blame my sleep. Turns out my basal was off by 0.2 units. One tweak. 40-point drop. And the gastroparesis thing? I had it for 8 years before anyone checked. My GI doc said, 'We see this all the time.' Why didn’t my endo? Because they’re not trained for it. Knowledge gaps kill. This post? It’s a lifeline.

steve sunio

u think u smart? u got diabetes? u checkin ur sugar? no. u just read article. u think u help? u just talk. u lazy. u rich. u american. u dont know real struggle. in nigeria, we use lemon juice and bitter leaf. works better than insulin. u dont believe? u stupid.

Joanne Tan

I’ve been using a CGM for 6 months and it changed my life. I didn’t realize how often I was spiking after lunch-like, 220+ after a turkey sandwich. Now I know to walk for 10 mins after eating. Tiny habit. Huge difference. Also, hydration is everything. I used to drink soda because I was thirsty. Now I drink sparkling water with lime. Feels like a treat. And I’m alive. 💪

Reggie McIntyre

Hyperglycemia is like a slow-motion explosion. You don’t hear the fuse lighting. You just wake up one day with your body on fire and no idea why. I used to think 'I’ll check tomorrow.' Then I got dizzy during a Zoom call. My glucose was 387. I cried. Not because I was scared-I was mad. Mad that I ignored the signs. Mad that no one told me how quiet the warning bells are. Don’t be mad. Be aware. Be early.

Jack Havard

All this data is manipulated. Blood sugar isn't the issue-it's the insulin industry. The real crisis is the systemic suppression of natural glucose regulation. Fasting, movement, and time-restricted eating cure this. But they don’t sell CGMs. They don’t profit from 'education programs.' They profit from dependency. You’re being sold a problem to sell you a solution.

Gloria Ricky

I just want to say-this is so important. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen too many people wait until they’re in the ER. One woman said, 'I didn’t think it was that bad.' I held her hand. She was 41. She had HHS. She didn’t know she had diabetes. Please. Don’t wait. Even if you think you’re fine. Just check. One test. That’s all it takes.

Stacie Willhite

I’m not a diabetic, but my mom is. I read this and cried. She hides her numbers. Says she doesn’t want to 'be a burden.' I’ve started leaving little sticky notes on her fridge: 'I love you. Check your sugar.' It’s silly. But it works. Small things matter. So much.

Jason Pascoe

I’m from Melbourne and we’ve got a huge gap in rural diabetes care. People drive 3 hours for insulin refills. No CGMs. No education. I helped set up a mobile clinic last year. We tested 147 people. 38 had never been diagnosed. One 62-year-old man had a glucose of 712. He thought he was just 'drinking too much tea.' We got him help. But how many more are out there? This isn’t just medical-it’s social. We need equity, not just algorithms.