When a generic drug hits the pharmacy shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy. But behind every generic pill is a rigorous scientific process designed to prove it works exactly like the brand-name version. That process is called a bioequivalence study. It’s not guesswork. It’s not marketing. It’s a tightly controlled, data-driven experiment that ensures your generic medication delivers the same active ingredient, at the same rate, into your bloodstream as the original. If this step fails, the generic isn’t approved. And if it passes, you can trust it just as much as the brand name.

Why Bioequivalence Studies Exist

Before the 1980s, companies had to run full clinical trials to prove a generic drug worked. That meant years of testing, thousands of patients, and costs so high that generic drugs rarely made it to market. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act changed that. It created a smarter path: instead of proving the drug works in patients, prove it behaves the same way in the body as the original. That’s where bioequivalence comes in. The goal is simple: if two drugs have the same active ingredient and release it into your blood at the same speed and amount, they’ll have the same effect. This isn’t just theory. The U.S. FDA has approved over 900 generic drugs each year based on these studies. And since 2010, generics have saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.6 trillion. Bioequivalence studies make that possible.The Core Design: Crossover Studies

Most bioequivalence studies use a crossover design. That means each volunteer takes both the generic (test) drug and the brand-name (reference) drug - but not at the same time. They get one first, then after a waiting period, they get the other. Half the group gets the generic first; the other half gets the brand first. This setup cancels out individual differences. If someone’s body absorbs drugs slowly, it affects both doses equally. That makes the comparison fair. The number of volunteers? Usually between 24 and 32 healthy adults. For simple drugs, that’s enough. But for drugs that behave unpredictably - like those with high variability in how people absorb them - studies may need 50 to 100 people. The European Medicines Agency and Japan’s PMDA require more complex designs for these cases, often using four periods instead of two.The Washout Period: Giving the Body Time to Reset

Between doses, there’s a washout period. This is critical. If the first drug is still in your system when you take the second, you can’t tell which one is doing what. The rule? Wait at least five half-lives of the drug. That’s the time it takes for half the drug to leave your body. For a drug with a 12-hour half-life, that’s 60 hours - or about 2.5 days. But for long-acting drugs, like some antidepressants or blood thinners, the wait can be weeks. One CRO professional told a Reddit user their study got delayed by three months because they underestimated the washout for a drug with a 72-hour half-life. That mistake cost them $250,000.How They Measure What Happens in Your Body

After each dose, blood samples are taken - usually 7 to 12 times over 24 to 72 hours. The first sample is before the drug is given (baseline). Then they catch the rise: one sample just before the peak concentration (Cmax), two around the peak, and three during the decline. Sampling continues until the area under the curve (AUC) captures at least 80% of the total drug exposure. For most drugs, that’s 3 to 5 half-lives. The blood is analyzed using highly precise methods - typically liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). These tools can detect tiny amounts of the drug, often down to nanograms per milliliter. The method must be validated to be accurate within ±15% (±20% at the lowest detectable level). If the lab’s method isn’t solid, the whole study can be thrown out. BioAgilytix’s 2023 report found that 22% of failed studies had issues with analytical methods, costing an average of $187,000 each.

The Two Key Numbers: Cmax and AUC

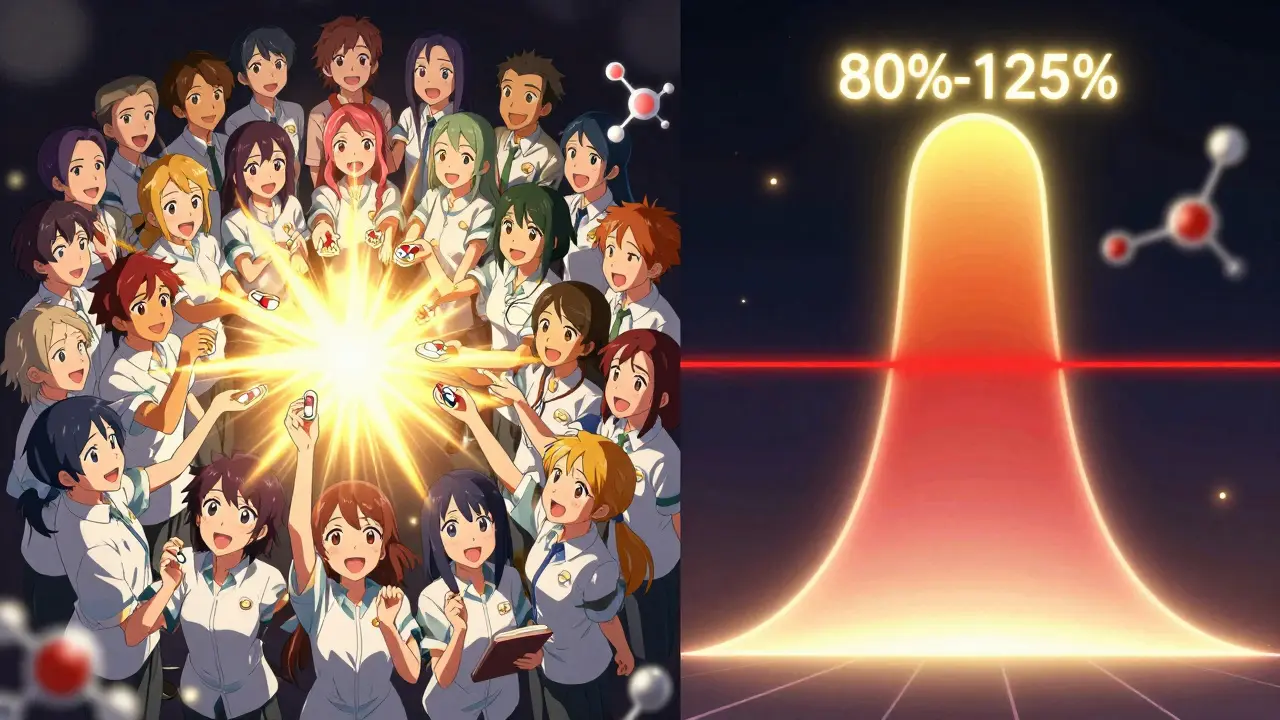

Two numbers decide if the drugs are bioequivalent: Cmax and AUC. - Cmax is the highest concentration of the drug in your blood. It tells you how fast the drug gets absorbed. A generic with a much lower Cmax might take longer to start working. - AUC(0-t) is the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. It tells you how much of the drug actually gets into your system. If the AUC is lower, the generic might not be as effective. AUC(0-∞), which estimates total exposure beyond the last sample, is used when possible. But AUC(0-t) is the standard for approval.The Golden Rule: 80% to 125%

The acceptance criteria are strict - and the same worldwide. For both Cmax and AUC, the 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio (test/reference) must fall between 80.00% and 125.00%. That means the generic’s average exposure can’t be more than 25% higher or 20% lower than the brand. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, lithium, or digoxin - the window tightens to 90.00% to 111.11%. Even small differences here could be dangerous. The FDA issued this stricter rule in 2019 after cases where slight changes in blood levels led to adverse events. Statistical analysis uses logarithmic transformation and ANOVA models to account for sequence, period, and subject effects. The math is complex, but the outcome is simple: either the numbers fit the range, or they don’t.What Happens If It Fails?

Failure isn’t rare. About 10% to 15% of bioequivalence studies don’t pass on the first try. Reasons? Poor sampling timing, too short a washout, or analytical errors. One study failed because the lab used an unvalidated assay. Another failed because the generic tablet dissolved too slowly in the stomach. When a study fails, companies usually go back to the drawing board. They might reformulate the tablet, change the manufacturing process, or run a pilot study first. Dr. Jennifer Bright, former director of the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs, said pilot studies reduce failure rates from 35% to under 10%. That’s why smart companies invest in them. Take Alembic Pharmaceuticals’ 2022 rejection of their generic version of Trulicity. The Cmax values were inconsistent across multiple studies. The drug is a GLP-1 agonist - complex, injectable, and sensitive to formulation changes. The company had to restart the entire development process.

When Crossover Isn’t Enough

Not all drugs can be studied this way. For drugs with half-lives longer than two weeks, a crossover design would require volunteers to be in the study for months. That’s impractical. Instead, researchers use parallel studies: one group gets the generic, another gets the brand. They compare the groups directly. But this needs more people - often 80 to 120 - because individual differences aren’t canceled out. For modified-release drugs (like extended-release pills), multiple-dose studies are used. Volunteers take the drug daily for several days to see how it builds up in the body. Some drugs don’t even need blood tests. For topical creams or inhalers, the FDA now requires clinical endpoint studies - measuring actual patient outcomes like skin healing or lung function. For certain BCS Class I drugs (highly soluble, highly permeable), in vitro dissolution testing alone can be enough. That’s called a biowaiver. In 2022, 27% of approved generics got approval this way.The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Bioequivalence studies are the invisible backbone of affordable medicine. Without them, generics wouldn’t exist. Or worse, they’d be unsafe. Every time you pick up a generic prescription, you’re benefiting from thousands of hours of scientific work - from chemists in labs, to statisticians crunching numbers, to volunteers giving blood samples. Regulatory agencies like the FDA, EMA, and PMDA don’t approve these studies lightly. They review every detail: the protocol, the analytical method, the statistical plan, even the batch numbers of the drugs used. The FDA received over 2,500 bioequivalence submissions in 2022. The median review time? Just over 10 months. And the demand is growing. As blockbuster drugs like Humira and Enbrel lose patent protection, the number of bioequivalence studies is rising. The global market for these studies hit $1.87 billion in 2022 and is expected to grow over 7% per year through 2030.What’s Next?

The field is evolving. Modeling and simulation - using computer models to predict how a drug behaves - are becoming more common. The FDA now accepts PBPK models (physiologically based pharmacokinetic models) for some complex generics. Real-world evidence is also being explored. The agency’s 2024-2028 plan aims to reduce study requirements for certain generics by 30% using data from electronic health records. But the core hasn’t changed. Bioequivalence isn’t about being cheaper. It’s about being the same. And that’s what keeps patients safe - and healthcare affordable.What is the main goal of a bioequivalence study?

The main goal is to prove that a generic drug releases the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. This ensures the generic works the same way in the body, even though it may look or cost different.

How many people are usually in a bioequivalence study?

Most studies involve 24 to 32 healthy volunteers. For drugs with high variability or long half-lives, studies may include 50 to 100 people. Parallel studies, used for very long-acting drugs, often require 80 to 120 participants.

Why is the washout period so important?

The washout period ensures the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second is given. If traces remain, they can interfere with measurements. The standard is five half-lives of the drug - which can range from days to weeks depending on the medication.

What are Cmax and AUC, and why do they matter?

Cmax is the highest concentration of the drug in the blood, showing how fast it’s absorbed. AUC measures the total drug exposure over time, showing how much gets into the system. Both must fall within 80%-125% of the brand-name drug’s values for the generic to be approved.

Can a bioequivalence study fail? What happens then?

Yes, about 10%-15% of studies fail on the first try. Common reasons include incorrect sampling times, inadequate washout, or flawed lab methods. When this happens, companies usually reformulate the drug or run a pilot study to fix the issue before trying again.

Are there alternatives to blood tests in bioequivalence studies?

Yes. For some drugs - especially those that act locally, like inhalers or creams - clinical endpoint studies are used, measuring real patient outcomes. For highly soluble drugs, in vitro dissolution testing alone can be enough, called a biowaiver. But for most systemic drugs, blood tests remain the gold standard.

Comments (14)

Naomi Walsh

Let’s be real-most people have no idea how meticulously regulated generics are. The 80-125% confidence interval isn’t some arbitrary number; it’s the result of decades of pharmacokinetic refinement. The FDA doesn’t just rubber-stamp this stuff. They audit labs, validate assays, and cross-check batch records. If you think your $4 generic is ‘just a copy,’ you’re underestimating the entire infrastructure behind it. This isn’t pharmaceutical magic-it’s regulatory science at its most disciplined.

And don’t even get me started on those ‘biowaivers’ for BCS Class I drugs. That’s the pinnacle of efficiency: replacing human blood draws with dissolution profiles validated against in vitro-in vivo correlations. Elegant. Efficient. Necessary.

Meanwhile, some countries still require full clinical trials for generics. It’s not just inefficient-it’s unethical when you consider the billions wasted. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a triumph of evidence over bureaucracy. Shame more people don’t know that.

Nidhi Rajpara

It is important to note that bioequivalence studies are conducted under strictly controlled conditions, and the statistical methodologies employed are in accordance with international guidelines such as ICH E9 and E14. The geometric mean ratio, logarithmic transformation, and ANOVA models are not merely convenient tools-they are scientifically mandated approaches to ensure internal validity. Moreover, the washout period of five half-lives is not a suggestion but a regulatory requirement codified in the FDA’s 2021 guidance document on bioequivalence studies.

Furthermore, the use of LC-MS/MS for quantification is non-negotiable in modern studies due to its specificity and sensitivity. Any deviation from these standards renders the entire dataset invalid. It is imperative that stakeholders understand that this is not a commercial exercise but a public health safeguard.

Donna Macaranas

Wow. I never realized how much science goes into something I just grab off the shelf. I always thought generics were just cheaper versions, but this makes me feel way better about taking them. Thanks for laying it out so clearly.

Also, 1.6 trillion saved? That’s insane. I’m gonna start telling my friends about this next time they complain about generics.

June Richards

So you’re telling me I paid $200 for a brand-name pill for 3 years and now I can get the same thing for $4? 😏

And the FDA approves this? Sure. 😂

Meanwhile my cousin’s aunt’s neighbor’s dog got sick from a generic. Coincidence? I think not. #GenericScam

Jaden Green

It’s fascinating how the entire system hinges on a 90% confidence interval between 80% and 125%. A 25% variance in bioavailability is not trivial-it’s a statistical loophole disguised as scientific rigor. The assumption that Cmax and AUC are sufficient proxies for clinical equivalence is deeply flawed. What about interindividual variability? What about long-term metabolic effects? What about drug interactions in polypharmacy patients? These studies are conducted on healthy 20-somethings with no comorbidities-how is that extrapolated to the elderly, the renally impaired, or those on ten different medications?

The FDA’s approval process is a monument to regulatory capture disguised as efficiency. The real cost isn’t the $187,000 failed studies-it’s the patients who suffer because the system prioritizes speed over safety. And yet, we celebrate this as progress. How sad.

Lu Gao

80–125%? That’s wild. So a generic could be 25% stronger and still be approved? 🤯

Meanwhile, I’m over here taking my blood pressure med and wondering if I’m getting the ‘lite’ version or the ‘turbo’ version. 😅

Also, biowaivers for BCS Class I drugs? That’s like saying ‘this saltwater tastes the same as ocean water’ and calling it science. 🌊🧪

Angel Fitzpatrick

They say bioequivalence studies are ‘rigorous.’ But let’s be honest-this is all just a theater. The same corporations that make the brand-name drugs own the CROs that run the bioequivalence trials. The labs? Mostly outsourced to India and China. The volunteers? Paid $150 to lie in a bed for 72 hours and drink a pill. The FDA? Overworked, underfunded, and too cozy with Big Pharma.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘biowaiver’ loophole. You think they’re really testing dissolution profiles against real human absorption? Nah. They’re using predictive models built on data from the 90s. It’s all smoke and mirrors. The real goal? Make generics cheap enough to keep the masses docile while the pharmaceutical oligarchs rake in billions on the next blockbuster.

They call it science. I call it control.

Nicki Aries

This is one of the most important things I’ve read all year-and I don’t say that lightly. I work in healthcare administration, and I’ve seen how much fear and misinformation surrounds generics. People think they’re ‘inferior’-but this? This is why they’re not. This is why they’re safe. This is why they’re the reason millions can afford insulin, statins, and antibiotics.

Every single person who’s ever said, ‘I won’t take a generic’-you’re not being cautious, you’re being ignorant. And that ignorance is costing lives.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it everywhere.

Melissa Melville

So basically, the government says, ‘Hey, this pill looks different, costs less, but acts the same?’

And then we all just… believe them?

Wow. That’s the most American thing I’ve ever heard. 🇺🇸😂

Bryan Coleman

One thing people don’t talk about: the volunteers. These are real people-students, gig workers, retirees-who give up weeks of their lives for $500. They get poked, they get blood drawn, they have to stay in a hospital-like facility with no windows. And then they get thanked with a thank-you card and a $10 gift card to Walmart.

They’re the unsung heroes of this whole system. I’ve volunteered twice. It’s boring as hell, but I know I’m helping. So yeah-respect the humans behind the data.

Naresh L

It’s interesting how we’ve reduced human physiology to two numbers: Cmax and AUC. We measure absorption as if the body were a beaker, not a living, adaptive system. What of circadian rhythms? Gut microbiota? Genetic polymorphisms in CYP enzymes? These variables are averaged out in the name of statistical efficiency-but biology doesn’t average. It adapts.

Perhaps the real question isn’t whether generics are bioequivalent-but whether we’ve simplified medicine too far in our quest for cost-efficiency. Is sameness always safety? Or are we trading nuance for convenience?

Sami Sahil

Bro this is so cool! I never knew so much science went into those little pills I take for my cholesterol. You’re basically a superhero for making medicine affordable. 🙌💊

Also, 1.6 trillion saved?! That’s like buying 160 million pizzas and not paying for them. Mind blown.

franklin hillary

Let me say this loud and clear: bioequivalence isn’t about copying-it’s about replicating function. It’s the difference between a copy of a symphony and a live orchestra playing the same notes with the same timing. The sheet music is the same, the instruments are different, but the experience? Identical.

And yes, 10% fail. So what? That’s not failure-that’s quality control. If you’re not failing sometimes, you’re not pushing hard enough.

This is how science works. Not by magic. Not by hype. By measurement. By patience. By people who care enough to get the numbers right.

Genius. Pure genius.

Bob Cohen

Just read this whole thing. I’m a nurse. I’ve seen patients panic because their pill changed color. I’ve had to explain this exact process-over and over.

Now I have a 10-minute read I can send them. Thank you. This is the kind of content that saves lives. Not just money. Lives.