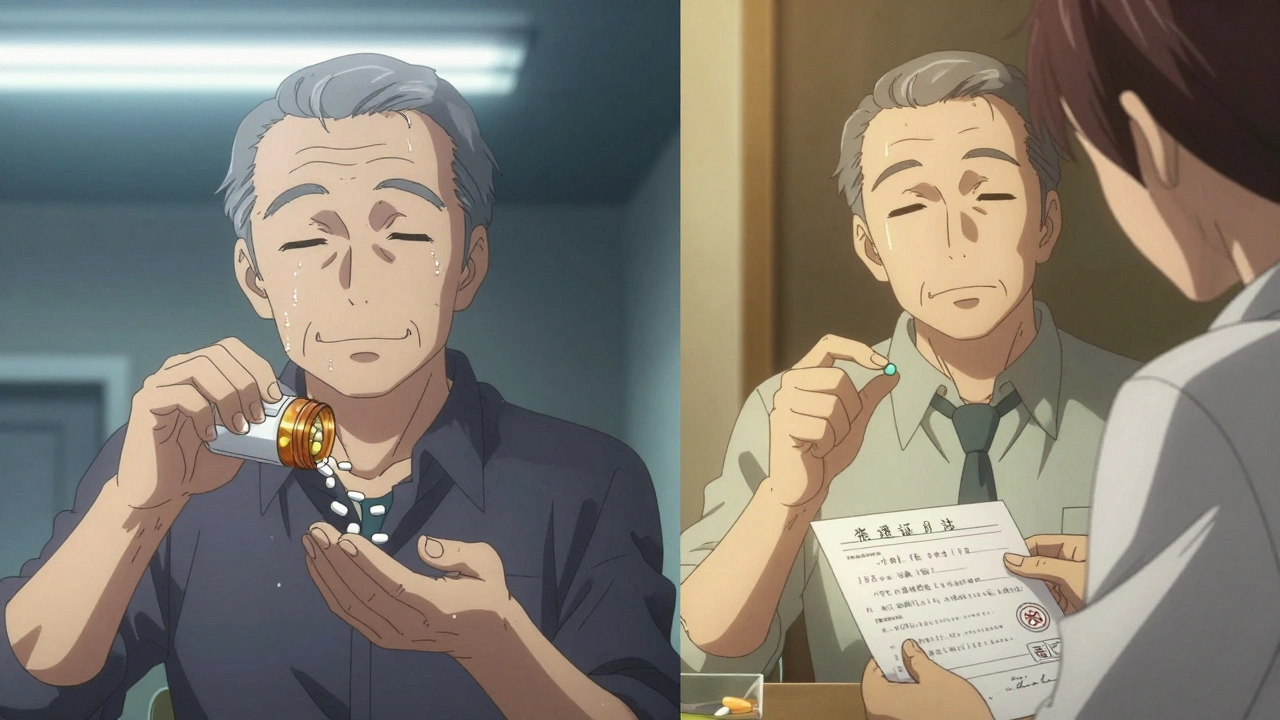

Imagine taking your medicine because the label says "take once a day"-but it actually means "take eleven times a day". That’s not a horror movie. That’s what happens when pharmacies use bad translation tools on prescription labels. For millions of people in the U.S. who don’t speak English well, a simple mistranslation can turn life-saving medicine into something dangerous. And it’s happening more often than you think.

Why Prescription Labels Get Translated Wrong

Most pharmacies don’t hire real translators. Instead, they rely on computer programs to turn English labels into Spanish, Chinese, Vietnamese, or other languages. These programs don’t understand medical terms. They just swap words. And that’s where things go wrong. Take the word "once". In English, it means "one time." But in Spanish, "once" means "eleven." So if a label says "take once daily" and gets auto-translated, it becomes "tome once diario"-which tells someone to take the pill eleven times a day. That’s not a typo. That’s a medical emergency. Other common mistakes include:- "Twice daily" turning into "twice weekly"

- "With food" becoming "after food" or "before food"

- "Do not crush" translating to "crush before taking"

Who’s Affected? The Numbers Don’t Lie

About 25.5 million Americans have limited English proficiency. That’s one in eight people. Spanish speakers make up the biggest group-over 15 million. But there are also 1.35 million Chinese speakers, 535,500 Vietnamese speakers, and hundreds of thousands more who speak Arabic, Russian, Tagalog, and other languages. The problem isn’t just big cities. It’s everywhere. Rural clinics, small-town pharmacies, and chain stores all use the same flawed systems. And it’s getting worse. Between 2010 and 2022, the number of people with limited English skills grew by nearly 19%. A 2023 survey found that 63% of non-English-speaking patients felt confused about their medication instructions. Nearly 28% admitted they’d taken the wrong dose because of translation errors. Some didn’t realize they were taking too much. Others thought they were supposed to skip doses. Either way, the results are the same: hospital visits, bad reactions, and sometimes death.Where It’s Working: California and New York

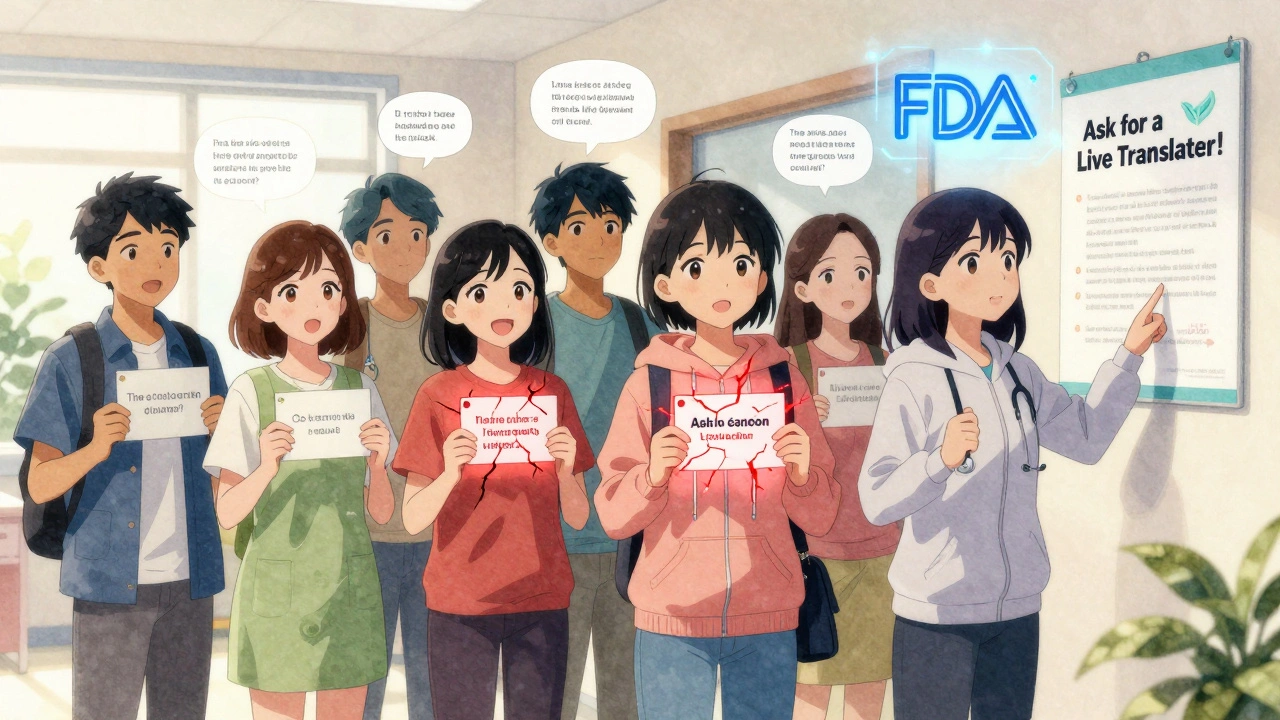

Not every state ignores this. California passed a law in 2016 requiring pharmacies to use certified medical translators for prescription labels. New York followed with similar rules in 2010. And the results are clear. A 2022 UCLA study showed a 32% drop in medication errors among Spanish-speaking patients in California compared to the rest of the country. ER visits related to prescription mistakes fell by 27%. That’s not luck. That’s policy. These states require:- Translations done by certified professionals-not machines

- Two people to check every label: one translator, one pharmacist

- Use of approved medical terminology (not casual translations)

What’s Being Done Now?

Big pharmacy chains are starting to catch up. Walgreens rolled out MedTranslate AI in late 2023. It uses artificial intelligence to suggest translations-but then a pharmacist reviews them. CVS Health launched LanguageBridge in early 2024 with the same model. Both say their error rates dropped by over 60% in pilot stores. The FDA also stepped in. In January 2024, they released new guidance asking pharmacies to use plain language on labels-short sentences, simple words, clear instructions. That makes translation easier and more accurate. The federal government is funding change too. In March 2024, the Department of Health and Human Services launched a $25 million grant program to help pharmacies buy translation tools and train staff. But progress is slow. A May 2024 government report found that 61% of federally funded health centers still don’t have certified translators for prescriptions. Many small pharmacies can’t afford the upgrades. And for languages like Hmong, Kurdish, or Bengali? Translation services are almost nonexistent.How to Get Help If Your Label Doesn’t Make Sense

You don’t have to accept a dangerous label. Here’s what to do:- Ask for a live translator. Say: "Can I speak with someone who speaks my language? I need to understand this label." Most major chains have phone or video interpreters available-even if they don’t offer printed labels in your language.

- Don’t trust the computer translation. If it looks odd, confusing, or too simple, it’s probably wrong. Compare it to the English version. Does "take two tablets twice daily" really say "take two tablets once a week"? That’s not a translation. That’s a mistake.

- Call your doctor or pharmacist. Ask them to explain the instructions in your language. Most will do it for free. If they don’t, ask to speak with a supervisor. You have a legal right to understand your medication.

- Use free translation tools wisely. Apps like Google Translate can help-but never rely on them alone. Type in the exact English instruction and compare it to the label. If they don’t match, question it.

- Report bad translations. Tell the pharmacy manager. File a complaint with your state’s board of pharmacy. And if you or someone you know was hurt because of a mistranslated label, contact the FDA’s MedWatch program. Your report helps change the system.

What You Can Do to Push for Change

If you speak a language other than English, you’re not alone. And you’re not powerless.- Join local advocacy groups that focus on language access in healthcare.

- Ask your state representatives to introduce a law like California’s.

- Share your story. Tell your friends. Post online. The more people talk about this, the harder it becomes for pharmacies to ignore it.

What’s Next?

Experts say that within the next 5 to 7 years, accurate prescription translation will be standard-not optional. Why? Because the cost of getting it wrong is too high. And the technology to fix it is already here. But change won’t happen by itself. It needs people to speak up. To ask questions. To demand better. Your life-or someone you love-could depend on it.Why do pharmacy labels sometimes say "once" when they mean "eleven"?

This happens because computer translation tools don’t understand context. The English word "once" (meaning "one time") is the same as the Spanish word for "eleven." Without human review, the system translates it literally, creating a dangerous error. Only certified medical translators can catch these false cognates.

Is it illegal for pharmacies to use machine translation on prescriptions?

In most states, yes-it’s legal, but not safe. Only California and New York require professional human translation for prescription labels. In other states, pharmacies can use automated tools, even though studies show they make errors in over half the labels. There’s no federal law yet, but the FDA is pushing for change.

Can I get my prescription label translated for free?

Yes. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, pharmacies receiving federal funding must provide language assistance at no cost. Ask for an interpreter over the phone or video call. You don’t need to pay. If they refuse, ask to speak with a manager or file a complaint with your state’s pharmacy board.

What languages have the worst translation problems?

Spanish has the most reported errors because it’s the most common non-English language and also the most commonly auto-translated. But for languages like Chinese, Vietnamese, Arabic, or Hmong, translation services are rare. Only 23% of major pharmacies offer labels in these languages, and when they do, they’re often done by untrained staff or bad software.

How do I know if my pharmacy uses professional translators?

Ask directly: "Do you use certified medical translators for your prescription labels?" Pharmacies that do will often mention it on their website or at the counter. If they say "we use software," ask if a pharmacist reviews the translations. If not, consider switching to a chain like Walgreens or CVS in states with strong language laws-or ask for an interpreter instead.

Comments (13)

Wendy Chiridza

This is such a critical issue and honestly it’s shocking it’s still this bad in 2024. I work in public health and we’ve seen patients end up in the ER because of mistranslated labels. It’s not just about convenience-it’s life or death. Why are we still letting pharmacies cut corners on this?

California’s law should be the national standard. Period.

Mark Gallagher

Oh please. You people act like this is some new crisis. I’ve been working in pharmacy for 20 years and this has always been a problem. But you want to blame automation? Blame the patients who refuse to learn English. If you can’t speak the language of the country you live in, don’t blame the system for your ignorance.

And don’t get me started on the $25 million grant. Taxpayer money wasted on translating ‘once’ into Spanish when people should just learn the word ‘una vez’.

Pamela Mae Ibabao

Okay but can we talk about how wild it is that ‘once’ means eleven in Spanish? That’s the kind of thing that makes you laugh until you realize someone’s kid might die because of it.

I had a neighbor who took her blood pressure med ‘once daily’ and ended up in the hospital because the label said ‘tome once diario’-she thought it was a typo and took it 11 times. She’s fine now but… yeah. That’s terrifying.

Also, Walgreens’ new AI system? Kinda genius. Not perfect but way better than the old junk. Progress is slow but it’s happening.

Gerald Nauschnegg

Guys. I’m not even mad. I’m just disappointed. I walked into my local CVS last week and asked for my prescription in Tagalog. They handed me a printout that said ‘take one tablet twice a week’ for a med that’s supposed to be twice a day. I showed them the English version. They said ‘oh that’s probably a glitch, we’ll fix it tomorrow.’

Tomorrow. Like it’s a typo on a grocery list. This isn’t a glitch. This is negligence. And it’s happening in every town, every state, every pharmacy chain that thinks ‘we’re too busy to care.’

Palanivelu Sivanathan

Oh my god, this is the most important thing I’ve read all year. I mean, think about it - language is a bridge, right? And when you break that bridge with a robot, you’re not just mistranslating words - you’re breaking trust. You’re breaking lives. I’m from India, we have 22 official languages and still, we know the power of human translation. Machines don’t have hearts. They don’t understand fear. They don’t know that ‘once’ could mean death. This isn’t about cost. This is about soul. And we’re losing it. We’re losing it every single day.

And the FDA? They’re late. So late. But not too late. We still have time. We still have hope. We still have each other.

Joanne Rencher

Ugh. Another virtue signaling post. People don’t speak English? Move back to their country. Why should I pay for someone else’s language barrier? I work two jobs and I don’t get free interpreters for my tax forms. Why should pharmacies?

Also, ‘once’ = eleven? That’s hilarious. If you can’t even learn basic vocabulary, maybe you shouldn’t be taking medicine.

Erik van Hees

Let me break this down for you real quick. The FDA’s new guidance? It’s a bandaid. The real problem? The entire healthcare system is built on efficiency, not safety. They don’t care if you live or die - they care if the label prints in under 10 seconds and costs less than a coffee.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘MedTranslate AI’ nonsense. AI doesn’t understand context. It doesn’t know that ‘crush’ in medical terms means ‘don’t crush.’ It just sees ‘crush’ and says ‘crush.’ That’s not innovation. That’s laziness with a tech label.

Real solution? Hire bilingual pharmacists. Pay them. Train them. Stop outsourcing safety to robots. It’s that simple.

Cristy Magdalena

I just cried reading this. Not because I’m emotional - but because I remember my abuela. She took her insulin ‘once daily’ because the label said ‘tome una vez al día’ - and she thought it meant ‘one time total.’ She didn’t take it for three days. She ended up in the ICU.

They told her it was her fault for not asking. But how was she supposed to know? No one explained it. No one checked. No one cared.

I’m not angry anymore. I’m just… tired. Tired of being told it’s my fault that my grandmother almost died because a computer thought ‘once’ meant ‘eleven.’

Adrianna Alfano

My mom’s label said ‘take before meals’ but the Spanish version said ‘take after meals’ - she started getting dizzy every time she ate. I didn’t catch it until her doctor asked why she was having hypoglycemia after lunch.

When I complained to the pharmacy, they said ‘we use the best software available.’ I asked if they’d ever had a real person read it. They said no.

So I started translating all my family’s labels by hand. I take screenshots, paste them into Google Translate, then cross-check with the English version. It takes 10 minutes per script. But it saves lives.

If you’re reading this and you speak another language - please, do this for your family. Don’t wait for someone else to fix it. We have to fix it ourselves.

Casey Lyn Keller

Let’s be real - this is all part of the Great Translation Conspiracy. The government wants to flood the country with non-English speakers so they can justify more funding, more bureaucracy, more control. The ‘once’ = ‘eleven’ thing? That’s not a mistake. That’s a test. A test to see how many people will blindly follow a label that says ‘take eleven times a day.’

Who benefits? The pharmaceutical companies. They know people won’t question it. They know we’re too distracted to care.

Wake up. This isn’t about language. It’s about control.

Jessica Ainscough

I’m not a doctor or a pharmacist, but I’ve been helping my neighbor translate her meds for a year now. She’s 78, speaks only Vietnamese, and her kids are all busy with work. I just sit with her, read the English label, and say it out loud in Vietnamese. Sometimes I write it down. Sometimes I call the pharmacist with her.

It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t make headlines. But it keeps her alive.

Maybe the real solution isn’t more laws or AI - it’s just us showing up for each other.

May .

This is insane and no one talks about it

Sara Larson

YES. YES. YES. 🙌 This needs to go VIRAL. I just shared this with my entire family group chat. My cousin just got her diabetes meds translated by a teenager at the pharmacy and she thought she was supposed to take it every 2 hours. She’s okay but… 😭

Let’s demand change. Let’s call our reps. Let’s post this everywhere. Let’s make sure no one else has to guess what their medicine does. ❤️ We got this. 💪